Testicular Cancer

Testicular Cancer

-

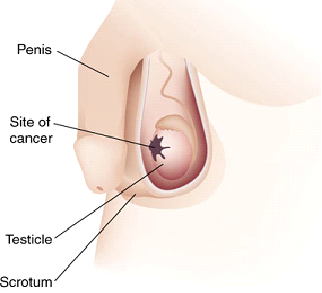

Testicular cancer is cancer that develops in the testicles, a part of the male reproductive system.

In the United States, between 7,500 and 8,000 diagnoses of testicular cancer are made each year. Over his lifetime, a man’s risk of testicular cancer is roughly 1 in 250 (0.4%). It is most common among males aged 15–40 years, particularly those in their mid-twenties. Testicular cancer has one of the highest cure rates of all cancers: in excess of 90 percent; essentially 100 percent if it has not metastasized. Even for the relatively few cases in which malignant cancer has spread widely, chemotherapy offers a cure rate of at least 85 percent today. Not all lumps on the testicles are tumors, and not all tumors are malignant; there are many other conditions such as testicular microlithiasis, epididymal cysts, appendix testis (hydatid of Morgagni), and so on which may be painful but are non-cancerous.

Signs and symptoms

-

Symptoms may include one or more of the following:

> a lump in one testis or a hardening of one of the testicles

> abnormal sensitivity (either numbness or pain)

> loss of sexual activity or interest

> sexual withdrawal

> A burning sensation, especially following physical activity.

> build-up of fluid in the scrotum or tunica vaginalis, known as a hydrocele

> a dull ache in the lower abdomen or groin, sometimes described as a “heavy” sensation

> lumbago – lower back pain

> An increase, or significant decrease, or sudden decrease in the size of one or both testes. The testicle with a tumor may be severely enlarged, as much as 3 times the original size. Simultaneously the other testicle may be shrunken in size, due to the tumor taking up the majority of the blood supply to the scrotum.

> blood in semen

> general weak and tired feeling

Diagnosis

-

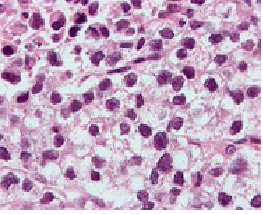

Micrograph (high magnification) of a seminoma. H&E stain.

The cardinal diagnostic finding in the patient with testis cancer is a mass in the substance of the testis. Unilateral enlargement of the testis with or without pain in the adolescent or young adult male should raise concern for testis cancer.

An incorrect diagnosis is made at the initial examination in up to 25% of patients with testicular tumors and may result in delay in treatment or a suboptimal approach (scrotal incision) for exploration

> Epididymitis or epididymoorchitis

> Hematocele

> VaricoceleThe differential diagnosis of testicular cancer requires examining the histology of tissue obtained from an inguinal orchiectomy specimen. Orchiectomy, rather than transcrotal biopsy, is preferred to reduce the risk of spill and thus the risk of metastasis, in the event that the tumor is malignant. For orchiectomy, an inguinal surgical approach is preferred.

Staging

- Stage I: the cancer remains localized to the testis.

- Stage II: the cancer involves the testis and metastasis to retroperitoneal and/or Paraaortic lymph nodes (lymph nodes below the diaphragm).

- Stage III: the cancer involves the testis and metastasis beyond the retroperitoneal and Paraaortic lymph nodes. Stage III is further subdivided into nonbulky stage III and bulky stage III.

- Stage IV: if there is liver and/or lung secondaries

Treatment

-

Surgery

While it may be possible, in some cases, to remove testicular cancer tumors from a testis while leaving the testis functional, this is almost never done, as the affected testicle usually contains pre-cancerous cells spread throughout the entire testicle. Thus removing the tumor alone without additional treatment greatly increases the risk that another cancer will form in that testicle . Since only one testis is typically required to maintain fertility, hormone production, and other male functions, the afflicted testis is almost always removed completely in a procedure called inguinal orchiectomy. (The testicle is almost never removed through the scrotum; an incision is made beneath the belt line in the inguinal area.) Most notably, since removing the tumor alone does not eliminate the precancerous cells that exist in the testis, it is usually better in the long run to remove the entire testis to prevent another tumor. A plausible exception could be in the case of the second testis later developing cancer as well. In the UK, the procedure is known as a Radical Orchidectomy.

-

Surveillance

For stage I cancers that have not had any adjuvant (preventative) therapy, close monitoring for at least a year is important, and should include blood tests (in cases of nonseminomas) and CT-scans (in all cases), to ascertain whether the cancer has metastasized (spread to other parts of the body). For other stages, and for those cases in which radiation therapy or chemotherapy was administered, the extent of monitoring (tests) will vary on the basis of the circumstances, but normally should be done for five years (with decreasing intensity). For the first year blood tests for tumor markers should be done monthly, and decreasing to once every three months in the years after. CT scans should be performed once every three months in the first year and decreasing to once every six months thereafter. The high cost of CT scans and the relative danger of the radiation involved both being factors in the relative infrequence with which tests are performed. CT-scans are performed on the abdomen (and sometimes the pelvis) whereas chest x-rays are preferred for the lungs as they give sufficient detail combined with a lower false-positive rate and significantly smaller radiation dose.

-

Fertility

A man with one remaining testis can lead a normal life, because the remaining testis takes up the burden of testosterone production and will generally have adequate fertility. However, it is worth the (minor) expense of measuring hormone levels before removal of a testicle, and sperm banking may be appropriate for younger men who still plan to have children, since fertility may be lessened by removal of one testicle[citation needed], and can be severely affected if extensive chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy is done.

-

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are two types of radiation therapy. External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer. Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer. The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

-

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly into the spinal column, an organ, or a body cavity such as the abdomen, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas (regional chemotherapy). Bladder cancer may be treated with intravesical (into the bladder through a tube inserted into the urethra) chemotherapy. The way the chemotherapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

-

Genetics

Most testicular germ cell tumors have too many chromosomes, and most often they are triploid to tetraploid. An isochromosome 12p (the short arm of chromosome 12 on both sides of the same centromere) is present in about 80 % of the testicular cancers, and also the other cancers usually have extra material from this chromosome arm through other mechanisms of genomic amplification.

Emergency Help line

Emergency Help line